The Usage of Commissive Speech Act in the Qur’an

ABSTRACT

One of the remarkable aspects of the Holy Qur’an is the use of diverse linguistic methods to convey a particular idea. This study aims to evaluate the commissive act in the Qur’an using Searle’s speech act theory, a theory useful in comprehending deeper semantic levels of holy scriptures. The study used a descriptive-analytical method, and the data were analyzed through a qualitative analysis of statistical results to answer the following questions: What linguistic forms does the Qur’an use to represent commissive speech acts? And what themes or topics are included in these commissive speech acts’ utterances? First, employing a desk research approach, the Qur’anic verses containing the commissive speech acts were selected based on syntactic, lexical, and semantic criteria. The distinguishing characteristics of each case were then identified, including the discursive structure of the act, the committed person, and the theme of the commitment. Finally, the relationship between the linguistic form and the theme of the speech acts was examined. The findings reveal that the Qur’an expresses commissive speech acts through four linguistic structures: oath, promise (al-wa‘d), threat (al-wa‘īd), and pledge; each includes divine and non-divine conceptions, and each has a unique characteristic. The quantitative comparison of these four shows that “promise” is the most commonly cited sub-speech act, distinguishing it from other linguistic forms. “Threat”, “oath”, and “pledge” are the other most frequently cited sub-speech acts.

1 . Corresponding author. E-mail address: f_tajabadi@sbu.ac.ir

Moreover, the evaluation of the speech agents and their status as aspects of the situational context reveals that the speech participants are not equal in terms of position and power, which is a decisive factor in the selection of linguistic forms. In all of these cases, the language structures and their intricacies, particularly modality (modal marking), illustrate the relationship between the linguistics style and power dynamics between the participants. The focus of the themes, domain, and frequency differ throughout the four categories mentioned above, with some overlap in certain instances.

KEYWORDS

discourse analysis, Searle’s speech act theory, commissive speech act, modality, the Qur’an.

1. Introduction

The holy Qur’an contains profound semantic layers, and the primary objective of reviewing this sacred text is to accurately comprehend its meanings or implications. To accomplish this valuable objective, this book can be examined from several angles, such as its speakers, its speech (lexicons), its content, and its communicative style. In this regard, pragmatics principles, which provide various methods for analyzing and comprehending linguistic data and guide the reader to a novel interpretation, can significantly facilitate understanding Qur’anic meanings. In addition, the pragmatics insights might offer a new door for Qur’anic researchers. Speech act theory, an essential part of modern linguistics throughout the past three decades, is one of the theories derived from pragmatics. Austin, an Oxford school philosopher, pioneered the concept of speech act in opposition to the logical positivists' philosophical assumptions (Vienna circle). Unlike these logicians, Austin argued that declarative or informative sentences are not the most prevalent types of utterances; hence, the transmission of information is not the main function of language, and proving the truthfulness or falsity of many statements is impossible. According to Austin, there are verbal sentences that do not have the potential to be true or false since their speakers aim for action rather than explain a subject or describe an emotion. He referred to such verbs as "action verbs." These verbs may be mentioned directly and explicitly in a sentence, which is called a "direct speech act." They can also be stated indirectly, which is referred to as an "indirect speech act". Austin’s linguistic theory consists of three connected acts: the "locutionary act,” "the illocutionary act,” and "the perlocutionary act.” Understanding these acts necessitates a reciprocal interaction between speaker and listener. After Austin, philosophers, and linguists like Schiffer, Fraser, Hancher, Bach, and Harnish investigated the nature and classification of speech acts. However, the most prominent modern speech act theory belongs to his student, Searle (1969), a famous contemporary philosopher. Searle thought that language not only describes a phenomenon but also performs it. He framed Austin's theory of speech acts within his philosophical viewpoint. He categorized action verbs into five content-based categories, later becoming famous as “Searle's Five Categories”. The aforementioned speech acts are as follows: 1) Assertive act, in which the speaker emphasizes his belief in the proposition's truthfulness. In fact, the speaker connects the content of such propositions to the outside world and shows his conviction through this form of speech act. 2) A directive act is when the speaker attempts to persuade the listener to do something by using specific statements. In other words, the speaker attempts to create conditions for performing actions with his words in order to adapt the outside world to the content of the proposition, which includes the listener's future action. 3) Declarative speech act announces new conditions to the audience or the outside world. The articulation of this kind of speech act results in a harmony between the language and the outside world. 4) Expressive act in which the speaker reveals his inner states and emotions to the audience. 5) Commissive act in which the speaker displays his commitment to accomplish something. Here, the speaker offers something to the audience through commissive acts of promising, vowing, guaranteeing, agreeing, presenting, etc., to do or leave something in the future; so, he commits himself to that task. After this brief introduction, it is obvious that speech act theory can enhance our understanding of the holy books’ discourse. This theory, in addition to considering intertextual features, also considers the external context of the speech, and as a result, by analyzing the meta-linguistic evidence governing the text, it reveals the nature of these pieces more systematically. Hence, the purpose of this research is to examine the specific discourse qualities of this act in the Holy Qur’an using the theory above and focusing on the commissive speech act to answer the following questions: 1) What linguistic forms does the Qur’an use to represent commissive speech acts? 2) What themes or topics are included in these commissive speech acts' utterances? To address these questions, after describing the background of the study and discussing the methodological approach in this article, the data is evaluated, and finally, the conclusion will be presented.

2- Research Background

In this section, we review the studies that have been undertaken regarding the Qur’anic speech acts, all of which are relevant to the issue at hand. Among the notable research conducted in this field are the following: By evaluating the idea of speech-action in the 30th section of the holy Qur’an, Abbasi (2013) found that directive, declarative, expressive, and commissive actions play essential roles in such verses. This research lists motivating speech acts and awareness, calling to think and attempting to attract attention as subgroups of the directive action used in commissive acts, and expressing focus, causation, motivation, occurrences, and presentation of the consequence as subgroups of the declarative speech act. Attempts to draw human attention to creation, regret, cursing, and advice have all been seen in expressive speech acts, whilst swearing has played an important part in commissive acts. Kazemi Abnavi (2013) evaluated the difference between Meccan and Medinan verses using Searle's five categories and determined that most speech acts utilized in Meccan and Medinan verses are assertive. Furthermore, the assertive speech act has the lowest frequency in Meccan verses, while the declarative act is not employed at all. On the contrary, the maximum frequency in Medinan verses is associated with the assertive speech act, whereas the lowest frequency is associated with the declarative act. Following Austin and Searle's theory of speech acts, Baj (2014) analyzed the directive speech acts of 500 Qur’anic verses. She classified the directive speech of these verses into two types: direct and indirect and determined that counseling has the most significant frequency in both groups, while alarm and scolding have the lowest. Delafkar et al. (2014) investigated the process of comprehending the speaker's aim of using this speech act while sketching the surrounding context of the scary discourse and analyzing the requirements for realizing this speech performance in the Qur’an. They also looked at the causes for the absence of other speech acts- such as encouragement, rebuke, and threat, for the audience. According to them, since God creates warns and God's speech is based on compassion and love for the audience, it is always expressed based on the audience's reasoning capacities, and the audience never feels forced in these cases but instead gets the necessary motivation to avoid danger through it. Jorfi and Mohammadian (2014) in their examination of the Qur’an’s 80th surah that the semantic link between this surah's verses, speech act, and syntactic style of the sentences is perfectly consistent with linguistics principles. In addition, the frequency of speech acts utilized in this surah, as well as its syntactic style, is directly linked to the social context. Furthermore, directive and expressive speech acts are the most prevalent in this surah. Tavakoli Sadabad (2015) investigated the theory of speech acts in 14 Medinan surahs and determined that the highest frequency is attributed to assertive acts (50 percent) and the lowest frequency is attributed to declarative acts (0.5 percent). Other speech acts’ percentages are in between. In analyzing the influence of context, and the speech act analysis in the Meccan and Medinan surahs, Hosseinimasoum and Radmard (2015) discovered that in the Meccan surahs, assertive speech acts have the maximum frequency and other acts have a lower number. As a result, it can be said that the main objective of these surahs was to communicate divine and Islamic teachings, as well as Islamic knowledge, which had a greater portion of Qur’anic content at the birth of Islam. The contrary is true in Medinan surahs, where speech acts connected to ordering and forbidding, encouragement and persuasion, and preaching and warning take precedence over assertive speech acts. These data clearly reveal that, in addition to the shift in situational context, the audience's religious affiliation (polytheist or Muslim) has affected the type of speech acts used. Evaluating the surah 78 “Al-Naba” and the content and style of the verses in this surah, Veysi and Deris (2016) discovered that the most considerable frequency of speech acts is connected to assertive and directive acts, which are related to preaching and warning the audience. According to the results of Modares' (2016) investigation on the commissive and rhetorical speech acts of the first 15 parts of the Qur’an, the most significant number of required acts was connected to threatening verses, and the lowest number was associated with oaths or swearing. Namdari (2017) found that in the speech act of preaching or gospel, the attempt to encourage the audience is optional, and the assertive action has the greatest frequency in the verses conveying the gospel, while the declarative and expressive actions are not employed. This is in contrast to the usage of expressive verbs in the warning-contained verses. Aghdai and Khakpour (2018) investigated the utterances in the Luqman surah by analyzing the interpretations and applying the content analysis approach. They determined that directive, assertive, and expressive acts are the most common, with just one example extracted for commissive action. The substance of the Qur’anic surah, namely the call to monotheism (al-tawḥīd) and afterlife (al-ākhirah), is fully in accordance with the role of the directive and assertive speech acts, but it falls far short of expressive, commissive, and declarative acts. While researching directive speech acts in Qur’anic surahs, Ahmadi Nargese et al. (2018) discovered that the directive speech act structure utilized in the Qur’an could be subdivided into nine distinct categories: interrogative, declarative, imperative, assertive, praise, slander, exclamatory, friendly, and interactive. Furthermore, these speech acts are typically utilized indirectly, demonstrating the presence of several dimensions and meanings in Qur’anic verses and encouraging people to think about and grasp the implications. Hasanvand (2019) concluded that, given the issues and substance of a Qur’anic surah Maryam, assertive and directive speech acts are employed more than other speech acts in the text. That was done to educate the audience about the history of the preceding civilizations. Dastranj and Arab (2020) found that in passages that directly and implicitly allude to Jihad, half of the instances include assertive speech acts, and then directive, declarative, expressive acts, and commissive have the most frequent. Taghavi (2020) evaluated Abraham's speech act against his opponents within the paradigm of Searle's theory and found that the assertive speech act, which was used to present and clarify the discourse of al-tawḥīd to expand and solidify its meaning, is the most common. Declarative speech acts, on the other hand, are seldom utilized. Reviewing this literature reveals that, although excellent research on the application of speech act theory has been conducted and strong findings have been achieved, none of these studies have concentrated on a kind of speech act descriptively and analytically with a holistic perspective. This fact emphasizes the significance and necessity of the present study.

3- Methodology and Theoretical Literature

This research attempts to investigate the employment of the commissive speech acts in the Qur’an using a descriptive-analytical approach based on Searle's (1969) speech act theory. To achieve the above objectives, each verse of the second 15 parts of the Qur’an's was studied utilizing the research desk approach and syntactic, morphological, and semantic clues. The passages containing the commissive act were then retrieved using language analysis. It is worth noting that the findings of Modares' (2016) study were utilized to extract data from the first 15 parts of the Qur’an. In the next part of the paper, each Qur’anic verse was tagged after the variety of commissive speech act, and its linguistic form was identified. Finally, we attempted to demonstrate the concepts these linguistic forms are utilized to represent based on the topic of each verse and the overall theme of Qur’anic surahs.

4- Discussion and Data Analysis

In this section, an effort is made to evaluate the data in accordance with the research questions in order to reach a comprehensive conclusion. To make the research more cohesive, we will evaluate the data in distinct sub-sections and based on different categories of commissive acts.

4-1- Oath

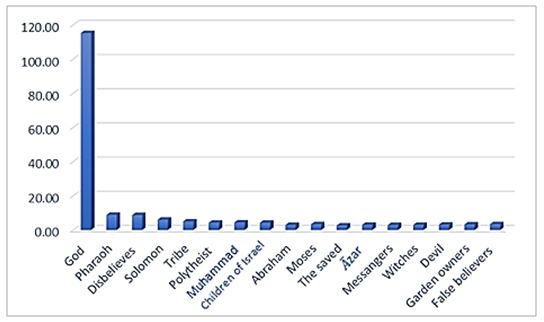

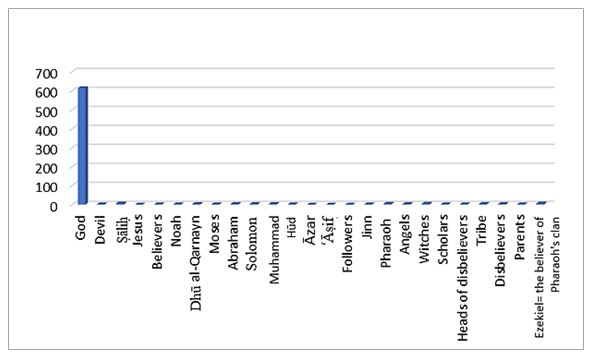

Oaths or swear expressions are one of the verbal forms of commissive acts. Oath is a linguistic stress on a concept that is important to the speaker or the listener. In this kind of commissive act, the speaker swears or takes an oath to show his dedication to a topic (negation or proof of an issue). Examining the verses containing commissive speech acts reveals that some of these acts are presented in the form of an oath. Oaths, which are essential linguistic elements of the Qur’an, have been employed openly (stated oath) or implicitly (implied oath). Implied oaths may be identified by several clues or indicators, particularly semantic implications. Consider the Qur’anic verse, "There is no soul save that it has a guardian over it"[1] (Q. 86:4). This speech act's verifying and reinforcing role is what makes it a fascinating example for verbal communication and action, as well as social discourse. Based on this, Qur’anic vows are classified as compulsory and affirmative (Faker Meybodi, 2004). An oath that a person takes to commit to doing or avoiding doing something is compulsory, such as "Said he, Now, by Thy glory, I will pervert them all together"[2] (Q. 38:82). An affirmative oath is one that is pronounced to verify or deny the truth of a topic; for example, "Nun. By the pen and what it writes"[3] (Q. 68:1-2). The oath structure has four components: the presenter of the oath, the object of the oath, the subject of the oath, and the particles or letters of the oath. This is the most prevalent syntactic formulation of the Qur’anic oaths (Ghafouri et al., 2015, 1:3516). In addition to this formulation, conditional structures (if clauses) that are regarded as modal components have been utilized for oaths in some cases. Here are some Qur’anic passages that prove this: “But he replied: 'Do you shrink away from my gods, Abraham? Surely, if you do not cease, I will stone you, so leave me for awhile” [4] (Q. 19: 46); “They said, "If you do not desist, O Lot, you will surely be of those evicted” [5] (Q. 26:167). The intriguing thing about this unique syntactic structure is that it can also be used to convey notions in ways that go beyond time; for example: “If you were to obey a human being like yourselves, then verily! You, indeed, would be losers” [6] (Q. 23:34). From a pragmatic perspective, the fundamental structure of the oaths has a larger spectrum of applicability, and an oath can be pronounced on any topic. However, the conditional nature of the oath has a restricted applicability and is only applied in a few circumstances. Nonetheless, from a rhetorical standpoint, the conditional construction of oaths has a stronger emphasis than the main structure (Mohammadi, 2020). For example, “And the fifth (testimony) should be that if he (her husband) tells the truth, Allah's Wrath will befall her” [7] (Q. 24:9). Moreover, an evaluation of the agent of speech (the one who uses oath), which is one of the three pillars of the situational context, reveals that the agent of this type of commissive act is limited to God (Allah), messengers, prophets (Solomon, Abraham, Moses, and Muhammad), devil, disbelievers, polytheists, false Muslims, particular groups or tribes like Children of Israel, witches, and notable people like Āzar (Figure 1). The agent of speech, often known as the participant, is an individual who performs a role in the text. Based on this, agents of oaths are classified as divine or non-divine. The first group performs three-quarters of all oaths. One thing to keep in mind while discussing the speech agents in this form of the commissive act is the absence of explicit reference to women as oath participants. Of course, this issue is the effect of the text's discursive context and should be studied in fields like anthropology and the sociology of language. On the other hand, evaluating the verses' content reveals that the range of the themes for which an oath is given is not very broad (Figure 2).

Figure1: the committed in oaths as the Qur’anic commissive speech acts It should be noted that all of the topics for which God has employed oath are pretty important. Such issues include the oneness of God (al-tawḥīd), the validity of the Qur’an, the origin of existence (genesis, creation), the occurrence of the Day of Judgment, the missions (the prophets' mission, the prophets' obligation), and God's total and limitless omnipotence.

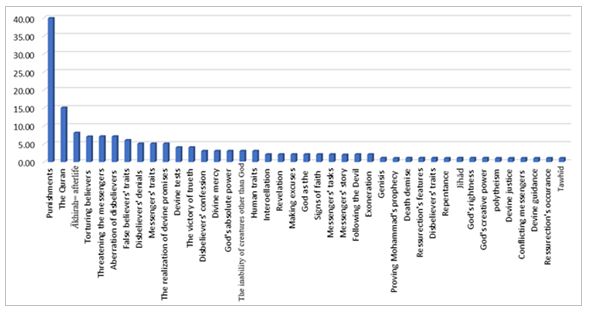

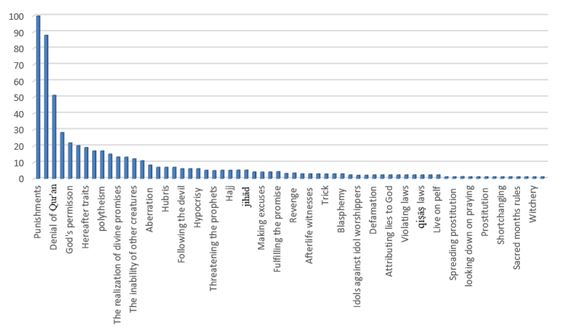

Figure2. The theme of the verses containing the commissive act of otah In general, all divine oaths, at least to some extent, include the concept of al-tawḥīd. The heavenly objective buried in this usage of these functions is for the audience to ponder about it more because they acknowledge the topic's significance. Another consideration regarding divine oaths is the broad spectrum of audiences, which is not seen in non-divine oaths. In other words, in all non-divine oaths (save evil’s oath), the utterance is addressed to a particular group at a given time and place. This restriction, however, is not reflected in divine oaths. Although these oaths can be used to address a specific person: “That I will fill Hell with you [Iblis (Satan)] and those of them (humankind) who follow you, together” [8] (Q. 38:85). They also can be used to address a specific group (“And by Allah, I have a plan for your idols – after ye go away and turn your backs” [Q. 21:57]). In such cases, they take a stand on their own, and their audience is humanity in general, without regard for time. Here is an example: “And (as for) those who work hard for us, we will most certainly guide them in our ways; and Allah is most certainly with the doers of good” [9] (Q.29:69).

4-2- Promise (al-wa‘d)

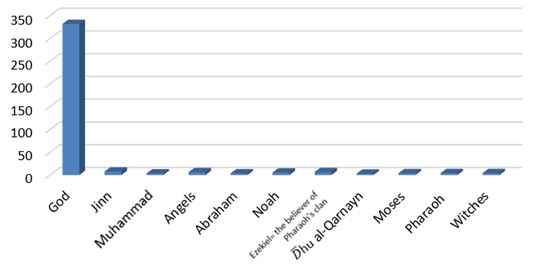

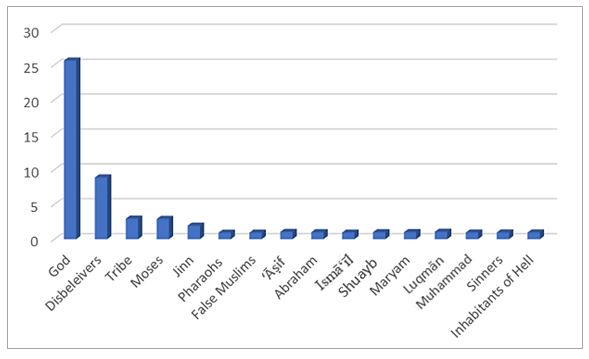

The literal translation of al-wa‘d is “promise” (Qorashi 1992, 7:227). The term al-wa‘d is used in the Qur’an for both “optimistic promise” and “deleterious promise” (al-Rāghib Iṣfahānī 1991, 875). However, al-wa‘d type’s commissive conduct in this article refers to the benefits that the committed offers to the believers or followers. In other words, since al-wa‘d contain good news for the audience, we only consider it positively. It is worth noticing that the linguistic tools employed for this act do not fall into any particular lexical category. As a result, the broad meaning of the linguistics tool is the resource that signals that speech belongs to al-wa‘d speech act category, not the tool’s type. This form of speech act entails accepting a voluntary commitment to accomplish something. The purposive and informative motives are two powerful aspects in the formation of this speech act. The speaker's purposive motivation indicates that he employs proper linguistic tools to attain his purpose (convincing the audience and proving the truth). The speaker's informative motive is to deliver fresh knowledge to the audience. The goal of conveying this form of discourse- which is utilized both explicitly and implicitly - is to ask, persuade or encourage the audience to embrace values, virtues, attitudes, and good deeds. They actually try to persuade or encourage believers to do good deeds or refrain from doing something undesirable. In our data, the commissive speech act is heavily intermingled with the directive act. The range of promise makers available in this form of Qur’anic commissive conduct is restricted (like the case of oaths). God, angels, jinns (supernatural beings) witches, prophets (Abraham, Noah, Moses, and Muhammad), and exceptional individuals (the believer of Pharaoh's clan, Pharaoh, Dhū al-Qarnayn) are examples of those who make promises. God, as predicted, has allotted the most considerable portion as the agent of speech in this form of the commissive act (Figure3). The frequent lexical co-occurrence of the terms "God" and "Allah" with the word al-wa‘d in various verses verifies this.

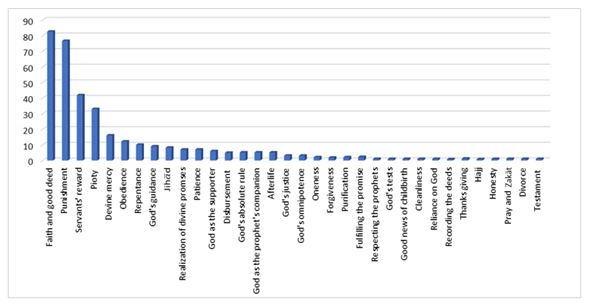

Figure3: the committed in the Qur’anic commissive acts (promise-type) In this speech act, the individual delivering the pledge is either higher or lower in position and position than the audience. However, in the Qur’anic linguistic style, the promise-giver is always in a higher social hierarchy than his listener. This style of Qur’anic speaking act's audience of promises may be classified into three groups: a) Has a distinct and targeted collective audience, as in the following verses: "Yes, and you will then genuinely be among those brought close (to me), he answered"[10] (Q. 26:42). b) Targeting a particular audience, as in "Zakariya! We send you good news of a son named Yahya, a name on which We have previously conferred honor"[11] (Q. 19:7) and "O my father! The knowledge that has not yet reached thee has come to me; therefore, follow me: I will lead thee in an orderly and straight path"[12] (Q. 19:43) c) has a hypothetical audience, such as: "Allah has promised pardon, and a large payment to those among you who believe and perform righteous works"[13] (Q. 24:55) and "Allah has promised forgiveness and a large wage to those among them who believe and do good deeds"[14] (Q. 48:29). The third group differs from the preceding two groups in that the speaker talks outside of time and space. This third category contains several heavenly promises and is distinguished by the fact that the object of promise is not limited to individuals of a specific time and location. Divine promises may be split into two kinds based on their purpose: a) The group in which the meaning of God's promise is a linguistic indication and a phrase that is expressly declared as a God's promise: for example, "And when the devout believers saw the clans, they said: This is what Allah and His messenger promised us. Allah and His Messenger are both correct. It did nothing except reaffirm their faith and resignation"[15] (Q. 33:22) b) The second category, which includes circumstances in which the meaning of the divine promise is the traditions and rules that flow as divine creations in the system of life, such as "O humanity! Allah's Promise is undoubtedly true. So don't let this world confuse you, and don't allow the biggest deceiver (Satan) deceive you concerning Allah"[16] (Q. 35:5). The divine promises in these passages, on the other hand, may be separated into two absolute and conditional categories based on the topic or substance of the words: a) Absolute promises in which God Almighty has not imposed any conditions on their fulfillment, such as the promise in the following verse to create the rule of the righteous: "Allah has promised those who have believed among you and done righteous deeds that He will surely grant them succession [to authority] on the earth just as He granted it to those before them, and that He will indeed establish for them [therein] their religion which He has preferred for them, and that He will undoubtedly substitute for them, after their fear, security, [because] they worship Me without associating anything with Me. Those who refuse to believe after that are brazenly disobedient"[17] (Q. 24:55). b) Promises that are conditional on accomplishing anything. The speaker uses a conditional phrase to offer a requirement for delivering his promise in this collection of promises. As a result, if task X is completed, God's promise Y, such as rain and Divine intervention, which is conditional on repentance and is described in the next verse, will be fulfilled after it (Elahidoost, 2021): “Ask your Lord for forgiveness; He is forgiving,' I added. He will pour down rain on you in torrents” [18] (Q. 71:10-11). A closer examination of the issues in this category of commitments (Figure 4) reveals that divine promises contain the ideas underlying anthropology, theology, and ontology, each of which has its own sub-category. These speech acts include ideological, social, individual, and cultural topics. Meanwhile, religious concepts such as faith and related issues, such as God’s oneness, prophecy, afterlife, and the like, take a more prominent place amid other divine promises. Faith and good deeds are the most often mentioned themes of heavenly promises. These two terms are used simultaneously about 100 times throughout the Qur’an (Mohadesi, 2009). In several texts, this pairing is presented in conjunction with divine promises. This interaction demonstrates the impact of faith and good works on fulfilling heavenly promises (Vahidnia and Hosseininia, 2020). The idea that God never fails to fulfill his promises is essential in many divine promises. God, in these circumstances, uses focus adjunct and luminous language are often used to persuade and comfort the listeners: “surely Allah will not fail (His) promise” [19] (Q. 3:9). The presenter uses modality in these verses to demonstrate the level of his devotion to the statement's authenticity[20]. The linguistic phrases of uncertainty are not employed in any of these Qur’anic verses. Heavenly father, on the other hand, has shown his entire confidence in his claims to the audience by adopting modal markings with the connotation of certainty.

Figure 4: The themes of verses containing the commissive acts of threat

4-3- Threat (al-wa‘īd)

The term al-wa‘īd (threat) appears six times in the Qur’an. This speech act is exclusively used in the Qur’an as frightening promises and to warn, awaken, and notify people of impending perils. In other words, unlike al-wa‘d, the commissive act of al-wa‘īd covers kinds of problems in which the committed person promises them to those who are in danger. It is worth noting that while compiling this section's data, not only the function of the term al-wa‘īd but also the meaning of the verse, including this term, was analyzed. Like Divine threat, al-wa‘īd is communicated in two ways: conditional and absolute. The verse "Verily, those who unjustly eat up the possessions of orphans, they eat up just a fire into their belly, and they will be burnt in the burning Fire!" [21] (Q. 4:10) is an example of a conditional threat. Lord plainly states in this verse that the outcome of usury is devouring hellfire. The verse Q.21:37, on the other hand, relates to torment in this world and says, "I will show you my portents, but beseech Me not to rush," [22] which is regarded as an absolute threat. The essential consideration here is that, in some cases, Qur’an combined the threat with divine promises in one verse. For example, "Those who consume usury will not rise unless they are driven insane by Satan's touch. This is because "commerce is like usury. However, Allah permitted commerce and forbade usury. Whoever refrains after receiving advice from his Lord may keep his previous earnings, and Allah decides his case. But whoever returns these are the inhabitants of the Fire, where they will remain indefinitely"[23] (Q. 2:275). In addition, both speech acts are mentioned in the following two verses "Allah condemns exploitation and blesses charitable organizations. Allah has no love for any unbeliever. Those who believe, do good deeds, pray regularly, and regularly give to charity will have their reward with their Lord. They will have nothing to fear or grieve"[24] (Q. 2:276-277). This point demonstrates that, in order to be more efficient, God has given his teachings to attract man's attention to worldly and eternal happiness, as well as the prevention of evil and devastation in the form of both positive and negative reports. Examining the data on the authors of speech reveals that God has provided a substantial part of the threats (92.5%), while prophets provided less than 10%, angels, Satan, jinns, particular persons, and so on (Figure 5).

Figure 5: the committed in the Qur’anic commissive acts (threat-type) Various groups have been threatened in these passages. Among them are unbelievers, fraudulent Muslims, Israelis, and shortchangers. A detailed examination of the performers' roles and their positions as the situational texture of the speech reveals that all of them had particular rankings, both in terms of social and economic standing, as well as power. This variable is regarded as a determining element in selecting such a language format. In other words, the speakers in all of these scenarios are unequal in terms of power and position. We observe the wide usage of modality in the verses including al-wa‘īd once again. Because the demonstrative element encompasses all parts of the discourse that are connected to the speaker's attitude or opinion and transfers the force of verbal power, it offers us a useful instrument for studying textual power relations (Kazemi Navaei et al., 2016). According to Halliday, modality is divided into two categories: modalization and modulation. We can immediately see that modulation is employed in these verses, as are varying degrees of confidence. The amount of assurance and strength that modal markers provide on words in these verses is directly proportional to their efficacy, for example: "And certainly, we shall test you with something of fear, hunger, loss of wealth, lives and fruits",[25] (Q. 2:155). In these instances, the speaker shows his strong faith clearly via active expression, which significantly influences the tone and discourse (Halliday & Matthissen 2004, 147-150). In these circumstances, the speaker highlights the superiority of his perspective over the listener while establishing a significant gap with him by applying strong and valuable personal pronouns and modal markers. In summary, the use of this mode of speech demonstrates the direction of power from top to bottom and transforms the discourse into a stage for the speaker to demonstrate authority. A review of the verses containing threats (Figure 6) demonstrates that, in addition to theological and ideological problems such as polytheism, unbelief, and rejection of the hereafter, which are largely individual, there are concerns that have a societal base and may constitute a threat. They play a significant role when it comes to human society. Among these issues are concerns such as shortchanging, usury, and hoarding, which lead the economic system to collapse, as well as arrogance, mockery, slander, entertainment, and spreading prostitution which lead the moral system to fall apart. Furthermore, problems like murder and retaliation (qiṣāṣ), which undermine social security and have very damaging repercussions and consequences for human communities, have been considered in these speech acts, and God has cautioned against them. The significant point is that, although God has specifically said that he does not violate promises in many verbal acts of promises, he has not done so in the case of threats. In this sense, viability and inviability are regarded to be differentiating features of these two sorts of acts.

Figure 6: The theme of the verses in the Qur’an with promise speech acts. Another key linguistic element of threatening verses is the range of language structures and linguistic components employed in this type of speech. Among these are interrogative structures, conditional structures, negative structures, structures with high certainty including modal verbs, and Iterative Structures, all of which indicate a threat to the audience. In these instances, the speaker attempts to communicate his ideology to the audience via different structures while also portraying his positive legitimacy and authority.

4-4- Pledge (al-‘ahd)

The aim of referring to a distinct part entitled Pledge (al-‘ahd), which comprises a very tiny quantity of the data, is to make the data analysis more consistent. Unlike the previous two parts, this section's examples do not include good news, persuasion, warning, or threats. For example, consider the following verses: “It guides to sound judgment, so we have believed in it, and we will never associate anyone with our Lord"[26] (Q. 72:2); "And those who disbelieve say: "We believe not in this Qur’an nor in that which was before it"[27] (Q. 34:31); “[Moses] said, "If I should ask you about anything after this, then do not keep me as a companion. You have obtained from me an excuse"[28] (Q. 18:76). In these series of verses, like in previous ones, God is at the center of discourse, with beings, prophets, and jinns following.

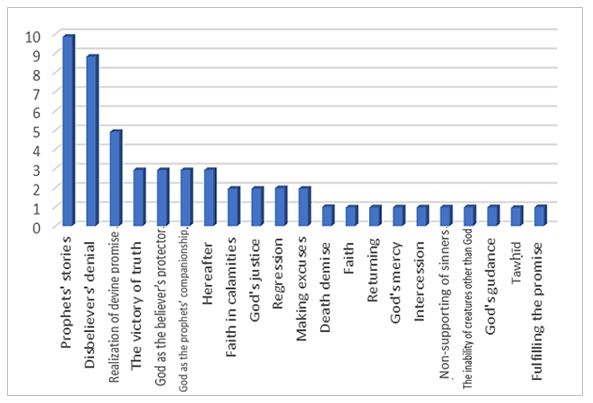

Figure 7: The committed in the commissive acts (promise type) A glance at the issues discussed in these verses reveals that topics such as God's oneness, God's justice, the fulfillment of divine promises, the hereafter, faith, the triumph of truth over falsehood, and similar topics are regarded as the primary topics. In this group of verses, the variety of linguistic structures is limited, and modal components such as modal verbs, attitude adverbials, modal transformations, vision verbs, and syntactical mood are employed less frequently.

Figure 8: The theme of verses containing commissive speech acts in the Qur’an (pledge type)

5- Conclusion

This study investigated the usage of commissive acts in the Qur’an using the speech act theory. In commissive acts, the speaker seeks to affect the external world by acting out the sentence's contents. The examination of Qur’anic instances including commissive acts revealed that such acts are portrayed in four linguistic forms: oath, promise (al-wa‘d), threat (al-wa‘īd), and pledge (al-‘ahd). A considerable portion of commissive acts takes the form of promises. These findings corroborate Modares' (2016) study. Using these linguistic structures, the Qur’anic speakers demonstrate their commitment to the authenticity of the statements. In all of the cases reviewed, the speaker attempted to offer the most effective and convincing speech to the audience by creatively and intelligently employing different linguistic forms. These speech acts are uttered by God, prophets, angels, Satan, jinn, and humanity (public or private). God, as predicted, is the primary agent of speech in all of the preceding situations. This is because one of the essential factors for using commssive acts is that the speaker is fully authorized. Examining the thematic range of the verses having this sort of speech act reveals that they may be generally categorized into individual, societal, and ideological themes. Moreover, ideological themes, particularly those concerning monotheism and the afterlife, have taken the central stage. Following that, due to their importance and large positive and negative impacts on the general public, social themes have the greatest frequency. On the other side, a review of the framework defining the discursive environment of these verses indicates that there is no evidence of power equality among the participants of the conversation, which is a reason for choosing this kind of speech act. Different linguistic elements, such as modality, highlight this power inequality in these verses. Additionally, the absence of women as agents of speech is noticeable in all of the aforementioned examples. To put it another way, the discursive context is masculine-dominated. To explain this problem, it may be said that since the commissive speech act demands direct action by the person, and women lack executive authority or activity in the context of the examined verses, the speech acts are usually performed by men. Moreover, a review of the linguistic structures utilized in the four stated categories reveals that the data connected to the threat type's commissive acts has the largest structural variation, followed by promises, oaths, and pledges. In addition to the little difference in data between groups, which might be one of the causes of this issue, another major cause is that the speech act of oath and promise are only characterized by stress. However, in thread-type commissive acts, the menacing component is also included in the speech and the Qur’an has used different linguistic facilities or complexities to explain it.

References

Abbasi, M., (2013). Investigation of speech acts in the translation of surah 3 of the Holy Qur’an based on Austin (1962) and Searle's (1969) theory. Master thesis. Faculty of Literature and Humanities. University of Sistan and Baluchestan.

Aghdaei, F., Khakpour, H. (2018). Textural analysis of Surah al-Loghman based on Searl's Speech Action Theory. Religious Literature and Art, 3(10), 9-35. https://doi.org/10.22081/jrla.2019.50997.1182

Ahmadinargese, R., Gerjian, B., Naghizadeh, M. & Hosseini, S., (2017). Illocutionary Speech Acts in the Holy Qur'an. Literary Qur'anic Researchs, 6(2), 21-34.

Ahmed, Shabbir, (2016). The Qur’an as it explains itself (translation of the Qur'an). Florida. viewed from: https://archive.org/details/qxpvi-english_201810/mode /2up Al-Rāghib Iṣfahānī, H., (1991). Al-Mufradāt fī Gharīb al-Qur’an. Damascus: Dār al-Qalam.

Baj, R., (2014). Examining imperative acts in the verses of the Holy Qur'an based on Austin's (1962) and Searle's (1969) speech action theory. Master’s thesis. Faculty of Literature and Humanities. University of Sistan and Baluchestan.

Dastranj, F., Arab, M. (2020). The Application of Speech Act Theory in the Reading of Ayahs of Jihad. Historical Study of War, 4(2), 23-52. https://doi.org/ 10.52547/HSOW.4.2.23

Delafkar, A., Saneeipoor, M., Zandi, B. & Arjmandfar, M., (2014). The Analysis of the Structure of the Speech Act of Warning in the Holy Qur’an. Linguistic Research in the Holy Qur’an, 3(1), 39-60.

Elahidoost, H., (2021). The role of divine promises in the formation of civilization based on the verses of the Holy Qur’an. Qur'an Culture and Civilization, 1(1), 44-61.

Faker Meybodi, M. (2004). Analysis of the oaths of Quran. Qur’anic Reserches, 10(37-38), 314-327.

Ghafouri, K., et al, (2015). Dictionary of Qur’anic sciences. Qom: Islamic Sciences and Culture Academy. Halliday, M.A.K. & Matthissen, C., (2004). An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Oxford.

Hasanvand, S., (2019). Analyzing Surah Maryam Based on Speech Act Theory Emphasizing John Searle's Model. Literary Qur’anic Researches, 7(2), 45-65.

Hosseinimasoum, S. & Radmard A., (2015). The Effect of Tempo-spatial Context on Speech Act Analysis; Comparing the Frequency Speech Acts in Meccan & Medinan Surahs of Holy Qur’an. Language Related Research, 6(3), 65-92.

Jorfi, M. & Mohammadian, E., (2014). A survey of “Abas” surah with Michal Foucault’s model of discourse analysis. Literary Qur’anic Researches, 2(2), 9-26.

Kazemi Abnavi, M., (2013). Examining the difference between the speech acts of Meccan and Medinan verses based on Searle's classification of speech acts. Master thesis. Faculty of Literature and Humanities. University of Shiraz. Kazemi Navaei, N., Sojoodi, F., Fazeli, M. & Sasani, F., (2016). From Certitude to Doubt: A Social-Semiotic Study of the Evolution of the Heroine’s Modal Structures in Touba va Ma’nay-e Shab. Literary Criticism, 8 (32), 133-154.

Modarres, M., (2016). Evaluation of Rherotical & speech act of commitment in Qur’an 15 component. Master thesis. Faculty of Principles of Religion.

Mohaddesi, J., (2009). Action, the measure of faith. Farhang- e- Kosar, 78, 135-136.

Mohammadi, F., (2020). A Form of Oath with Conditional Construction in Persian. Persian Language and Iranian Dialects, 5(2), 125-143.

Namdari, A., (2017). Investigating Good Tidings in Some Verses of the Holy Qur’an from a Speech Act Theory Perspective. Western Iranian Languages and Dialects, 5(19), 103-118.

Qorashi, A, (1992). Qāmūs Qur’an. Tehran: Dār Al-kutub Al-Islāmīyah.

Searle, J., (1969). Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taghavi, H. (2020). Abraham discourse with opponents in the Qur'an Based on the classification of speech actions of Searle. Researches of Quran and Hadith Sciences, 17(2), 1-31. https://doi.org/10.22051/tqh.2020.26755.2509

Tavakoli Sadabad, L., (2015). Analysis of the speech act of the fourteen Medinan surahs of the Holy Qur’an based on Searle's theory. Master thesis. Faculty of Literature and Humanities. Ferdowsi University of Mashhad.

Vahidnia, F. & Hosseininia, S. M. R., (2020). The Semantics of the Word "Promise" and its Educational Implications in the Holy Qur’an. Educational Doctrines in Qur’an and Hadith, 6(1), 105-123.

Veysi, A. & Deris, F., (2016). A comparative study of the analysis of the context of Surah "Naba" in Tafsir al-Mizan and the findings of contemporary linguistics. Qur’anic Doctrines, 13(24), 81-108.

- ↑ إن کُلُ نَفسٍ لَمّا علَیها حافظ (الطارق/4)

- ↑ قال فبعزّتک لأغوینّهم أجمعین (ص/82)

- ↑ ن و القَلَم و ما یَسطرون. ما أنتَ بِنِعمة ربّک بِمَجنون (القلم/1-2)

- ↑ قَالَ أَرَاغِبٌ أَنْتَ عَنْ آلِهَتِي يَا إِبْرَاهِيمُ لَئِنْ لَمْ تَنْتَهِ لَأَرْجُمَنَّكَ وَاهْجُرْنِي مَلِيًّا (مریم/46)

- ↑ قَالُوا لَئِنْ لَمْ تَنْتَهِ يَا لُوطُ لَتَكُونَنَّ مِنَ الْمُخْرَجِينَ (الشعراء/167)

- ↑ وَلَئِنْ أَطَعْتُمْ بَشَرًا مِثْلَكُمْ إِنَّكُمْ إِذًا لَخَاسِرُونَ (المومنون/34)

- ↑ وَالْخَامِسَةَ أَنَّ غَضَبَ اللَّهِ عَلَيْهَا إِنْ كَانَ مِنَ الصَّادِقِينَ (النور/9)

- ↑ لَأَمْلَأَنَّ جَهَنَّمَ مِنْكَ وَمِمَّنْ تَبِعَكَ مِنْهُمْ أَجْمَعِينَ (ص/85)

- ↑ وَالَّذِينَ جَاهَدُوا فِينَا لَنَهْدِيَنَّهُمْ سُبُلَنَا وَإِنَّ اللَّهَ لَمَعَ الْمُحْسِنِينَ (العنکبوت/69)

- ↑ قَالَ نَعَمْ وَإِنَّكُم إِذًا لَمِنَ الْمُقَرَّبِين (الشعراء/42)

- ↑ يَا زَكَرِيَّا إِنَّا نُبَشِّرُكَ بِغُلَامٍ اسْمُهُ يَحْيَى لَمْ نَجْعَلْ لَهُ مِنْ قَبْلُ سَمِيًّا (مریم/7)

- ↑ يَا أَبَتِ إِنِّي قَدْ جَاءَنِي مِنَ الْعِلْمِ مَا لَمْ يَأْتِكَ فَاتَّبِعْنِي أَهْدِكَ صِرَاطًا سَوِيًّا (مریم/43)

- ↑ وَعَدَ اللَّهُ الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا مِنْكُمْ وَعَمِلُوا الصَّالِحَاتِ لَيَسْتَخْلِفَنَّهُمْ فِي الْأَرْضِ (النور/55)

- ↑ وَعَدَ اللَّهُ الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا وَعَمِلُوا الصَّالِحَاتِ مِنْهُمْ مَغْفِرَةً وَأَجْرًا عَظِيمًا (الفتح/29)

- ↑ وَلَمَّا رَأَى الْمُؤْمِنُونَ الْأَحْزَابَ قَالُوا هَذَا مَا وَعَدَنَا اللَّهُ وَرَسُولُهُ وَصَدَقَ اللَّهُ وَرَسُولُهُ وَمَا زَادَهُمْ إِلَّا إِيمَانًا وَتَسْلِيمًا (الاحزاب/22)

- ↑ يَا أَيُّهَا النَّاسُ إِنَّ وَعْدَ اللَّهِ حَقٌّ فَلَا تَغُرَّنَّكُمُ الْحَيَاةُ الدُّنْيَا وَلَا يَغُرَّنَّكُمْ بِاللَّهِ الْغَرُورُ (فاطر/5)

- ↑ وَعَدَ اللَّهُ الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا مِنْكُمْ وَعَمِلُوا الصَّالِحَاتِ لَيَسْتَخْلِفَنَّهُمْ فِي الْأَرْضِ كَمَا اسْتَخْلَفَ الَّذِينَ مِنْ قَبْلِهِمْ وَلَيُمَكِّنَنَّ لَهُمْ دِينَهُمُ الَّذِي ارْتَضَى لَهُمْ وَلَيُبَدِّلَنَّهُمْ مِنْ بَعْدِ خَوْفِهِمْ أَمْنًا يَعْبُدُونَنِي لَا يُشْرِكُونَ بِي شَيْئًا وَمَنْ كَفَرَ بَعْدَ ذَلِكَ فَأُولَئِكَ هُمُ الْفَاسِقُونَ (النور/55)

- ↑ فَقُلْتُ اسْتَغْفِرُوا رَبَّكُمْ إِنَّهُ كَانَ غَفَّارًا. يُرْسِلِ السَّمَاءَ عَلَيْكُمْ مِدْرَارًا (نوح/10-11)

- ↑ إِنَّ اللَّهَ لَا يُخْلِفُ الْمِيعَادَ (آل عمران/9)

- ↑ Modality can be defined as the speaker's attitude or viewpoint on the substance of a statement or the current state of affairs.

- ↑ إِنَّ الَّذِينَ يَأْكُلُونَ أَمْوَالَ الْيَتَامَى ظُلْمًا إِنَّمَا يَأْكُلُونَ فِي بُطُونِهِمْ نَارًا وَسَيَصْلَوْنَ سَعِيرًا (النساء/10)

- ↑ خُلِقَ الْإِنْسَانُ مِنْ عَجَلٍ سَأُرِيكُمْ آيَاتِي فَلَا تَسْتَعْجِلُونِ (الانبیاء/37)

- ↑ الَّذِينَ يَأْكُلُونَ الرِّبَا لَا يَقُومُونَ إِلَّا كَمَا يَقُومُ الَّذِي يَتَخَبَّطُهُ الشَّيْطَانُ مِنَ الْمَسِّ ذَلِكَ بِأَنَّهُمْ قَالُوا إِنَّمَا الْبَيْعُ مِثْلُ الرِّبَا وَأَحَلَّ اللَّهُ الْبَيْعَ وَحَرَّمَ الرِّبَا فَمَنْ جَاءَهُ مَوْعِظَةٌ مِنْ رَبِّهِ فَانْتَهَى فَلَهُ مَا سَلَفَ وَأَمْرُهُ إِلَى اللَّهِ وَمَنْ عَادَ فَأُولَئِكَ أَصْحَابُ النَّارِ هُمْ فِيهَا خَالِدُونَ (البقرة/275)

- ↑ يَمْحَقُ اللَّهُ الرِّبَا وَيُرْبِي الصَّدَقَاتِ وَاللَّهُ لَا يُحِبُّ كُلَّ كَفَّارٍ أَثِيمٍ * إِنَّ الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا وَعَمِلُوا الصَّالِحَاتِ وَأَقَامُوا الصَّلَاةَ وَآتَوُا الزَّكَاةَ لَهُمْ أَجْرُهُمْ عِنْدَ رَبِّهِمْ وَلَا خَوْفٌ عَلَيْهِمْ وَلَا هُمْ يَحْزَنُونَ (البقرة/276-277)

- ↑ وَلَنَبْلُوَنَّكُمْ بِشَيْءٍ مِنَ الْخَوْفِ وَالْجُوعِ وَنَقْصٍ مِنَ الْأَمْوَالِ وَالْأَنْفُسِ وَالثَّمَرَاتِ (البقرة/155)

- ↑ يَهْدِي إِلَى الرُّشْدِ فَآمَنَّا بِهِ وَلَنْ نُشْرِكَ بِرَبِّنَا أَحَدًا (الجن/2)

- ↑ وَقَالَ الَّذِينَ كَفَرُوا لَنْ نُؤْمِنَ بِهَذَا الْقُرْآنِ وَلَا بِالَّذِي بَيْنَ يَدَيْهِ (سبأ/31)

- ↑ قَالَ إِنْ سَأَلْتُكَ عَنْ شَيْءٍ بَعْدَهَا فَلَا تُصَاحِبْنِي قَدْ بَلَغْتَ مِنْ لَدُنِّي عُذْرًا (الکهف/76)